Executive Summary

Healthcare systems around the world differ – public, private or a mix of both public and private (like in India). With all the variance in healthcare delivery models, the risks to healthcare professionals remain universal: needle injuries to litigations to episodes of threats/ violence (verbal or physical).

Universal discussions in healthcare include accessibility, affordability, quality: a topic of increasing importance is the trust-deficit in the doctor-patient relationship. It may not just be patients, but a larger stakeholder universe including healthcare activists, media, government, payers (insurance), etc. The action of insurance companies withdrawing cashless facility at private hospitals in 2010, got my interest in this subject for research. One insight from that research: while people had their grievances with the healthcare system, doctors were ranked number one for respect amongst other professionals!

Over the decade, speaking to the stakeholders to identify a middle ground for doctor-stakeholder reconciliation and tracking the narrative from a mass communication perspective – media coverage, social media conversations, books, depiction in films and entertainment – the relationship is observed to be tilting adversely.

Both sides have their stance, which is hardening and widening the chasm. The situation is such that instances of violence in public health facilities are adding to the negativity about doctors, rather than supporting their stance or overall impression. In a recent research (2019) to understand the risk of violence against doctors in public health facilities, this researcher stumbled upon a public relations question – who is the custodian of doctor’s communication and thereby reputation? It may be a significant gap in the communication effort.

This article outlines the missing links in the doctor-stakeholder communications and proposes 7 action points for setting a middle ground. Post Covid-19 offers the opportunity to reset the doctor-stakeholder relationship.

Introduction

“True virtue is placed at an equal distance between the opposite vices” wrote Edward Gibbon in his magnum opus ‘The Decline and fall of the Roman Empire’, quoting the famous Aristotle maxim. In Aristotle’s philosophy, the opposite vices are characterized by deficiency and excess. If courage is a virtue, coward (deficiency) and rash (excess) are the opposite vices. This has resonance for the doctor-stakeholders (patients, care givers, healthcare activists, media, government, payers) relationship in the Indian healthcare ecosystem. If empathy is the virtue at the center in healthcare, with ‘reverence’ (unchallenged, deity like status) as the excess and ‘apathy’ the deficiency end, it’s anybody’s guess where the narrative is drifting today.

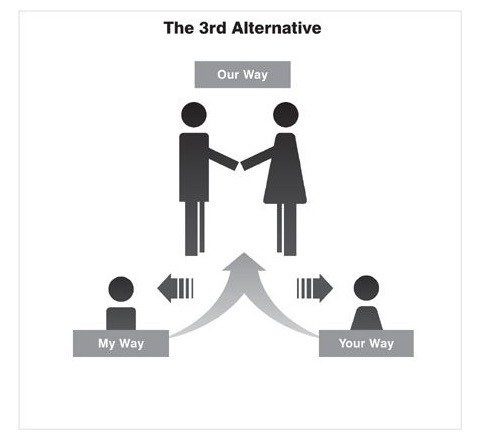

“Most conflicts have two sides” wrote Stephen Covey in ‘The 3rd Alternative’. According to him, we are used to thinking in terms of ‘my way’ and ‘your way’, in other words, every side has an agenda and that sustains conflict. The solution, the author proposes, is the 3rd alternative, the higher way, or what he calls ‘our way’. The route to the 3rd alternative is through the process of ‘synergy’: “the result when two or more respectful human beings determine together to go beyond their preconceived ideas to meet a great challenge”, he writes.

A matter of perspective

Imagine a frail, grey-haired, old woman crossing the road. A taxi hits her. She falls to the ground and is bleeding. What do you think people standing around will do?

This is a question I have asked at communication workshops with students and executives over the years. The answer is near unanimous (you may have guessed it!). There is a subsequent question to it: What if the signal was green, the driver was correct and the old lady was at fault?

The answer again is the same as the first one: the mob will hold the driver guilty and deliver some instant reaction. It brings us to the learning from the exercise: there is a public perception of reality, which may not be rational or factual, precipitating an action.

There is a following third question: Will the mob behaviour be different if the vehicle is an expensive car and the person at the wheel is presumably the owner? The answers start differing, with majority participants indicating that the mob will behave differently. What changed: the perception of vulnerability and power!

The above exercise has a bearing for doctors. They invariably carry a ‘burden of expectations’. Doctors agree that medicine was, is and will remain a noble profession. They recall the reverence that doctors enjoyed a few decades back and agree that the scenario has changed today. In numerous conversations and through analyzing media content, it is clear, doctors contend that there is a trust deficit. It is a stark reality not lost on the doctor community.

What is shaping the narrative?

From the doctors’ perspective, there are multiple factors shaping the narrative against them:

- Lack of communication: Medical professionals have been unsuccessful in communicating their side and challenge the widespread misinformation about them. Doctor bashing has become a dominant narrative without substantial grounds. This needs discussion and conversation to dispel misperceptions.

- Lack of credible support: Government and media, who can be neutral players, act as an adversary.

- Wrong portrayal: Media including films, TV programmes portray the medical profession in a negative light.

- Lack of time: Due to patient burden, doctors are spending less time with patients.

- Disconnect: Family doctor who was an important connect between patient and healthcare system is a dwindling tribe.

- Lack of understanding among stakeholders: Patients, other stakeholders do not understand and know of the tough life doctors live.

- Technology challenge: Online search is becoming a source of the chasm, as patients are getting a confused medley of information. On the other hand, patients are testing the veracity of doctor’s recommendations

A senior doctor summed up the doctor-patient relationship thus: “Years back, the doctor-patient relationship was one of reverence. Technology aided the diagnosis and prognosis. What the doctor said was accepted without a question. Now data and technology are revered, and the doctor questioned.” Another doctor explained this in terms of societal changes: “Complaints against doctors are registered under the Consumer Protection Act. The system forces a provider-consumer perspective, like a consumer durable or restaurant, to a relationship where faith and confidence are paramount. Accordingly, doctors now lay emphasis on evidence through tests, increasing healthcare costs!”

Activists retort highlighting instances of unnecessary procedures and tests. They feel, the information asymmetry that patients face in healthcare, with no verification mechanism, makes them vulnerable to exploitation. A flurry of books on corruption in healthcare have hit the stands in recent past, some of these written by doctors themselves. Actions by government on the policy front (like Prevention of Cut Practices in Healthcare Services Bill) brings the focus on medical community. Media coverage flows from such developments; social media amplifies it, further impacting the narrative adversely.

The adverse narrative – all mediums impacted.

Doctors acknowledge that films and television programs have impacted their credibility. A chat show by a film personality is specifically recalled as lopsided.

Films are an important indicator of the social milieu. Anand (famous for ‘babumoshai’) in the 1970’s, captures the dilemma faced by doctors and frustration they feel of social realities. But it is also a change indicator: starting with ‘Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani’ (1946) to ‘Gabbar Is Back’ (2015), the decline in doctors’ narrative is evident in Hindi films. In 70 years, the image of an upright, revered doctor was replaced by a doctor cheating the patient!

The perceptions are so shaped, that even in instances like violence in public hospitals, the blame lays on the doctors. Unlike private healthcare, where billing is a contentious issue and the reason many times for violence, public hospitals do not have similar issues. Consider the pattern of media coverage on the incidents of violence in public hospitals: reportage of what happened, protest or strike call given by doctors, views by subject experts on broader reasons for such violence like patient burden, lack of communication skills of doctors, the changing equation of doctor-patient relationship, trust deficit etc. The blame squarely comes on the medical fraternity.

When the narrative gets adverse, trust suffers.

My recent research on the subject of violence in public hospitals indicates a different view. There is lack of evidence of direct co-relation between issues of trust-deficit in doctor-patient relationship and the instances of violence in public health. “Emotional outbursts” is how participants (administration officials, activists, journalists) in the study described the instances of violence against doctors in public hospitals. The violence is spontaneous, not pre-planned, as per the available information. Senior doctors indicated that violence is not a new phenomenon, but the frequency has gone up recently and the younger generation of medical students has become vocal against it.

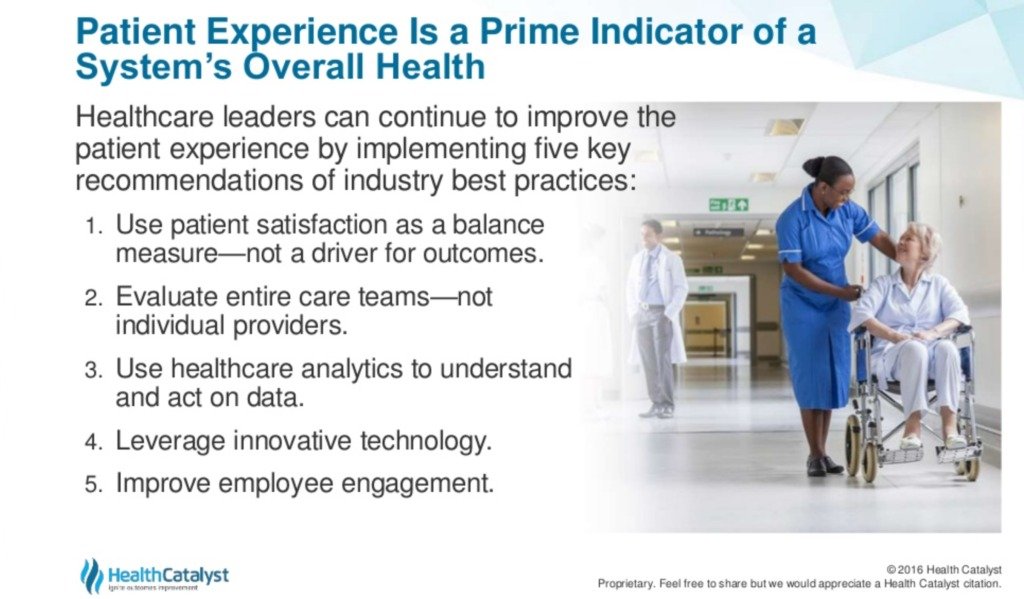

The media narrative is dominated by medical associations demand for bringing stricter legislation against the perpetrators of violence. Opinion among activists and journalists is divided on whether ‘stringent law’ will act as a deterrent against violence, with opponents highlighting many social evils that have a law to curb it, yet there is prevalence for the same. For them, the emphasis is to be on improving the overall experience of patients in public health (with lack of infrastructure). Absence of a long-term approach to deal with the issue of violence and the perception that medical associations speaking in self-interest, not public interest, may be an important challenge in their opinion.

Thinking about the future of medical practice.

Suffering in this environment are the young medical students. It is important to understand the life-cycle here. An 18-year-old enters medical school, undergoes about 5 years of gruelling studies and practice. Add more years for a post-graduation. These years have exposed them to serious matters of life and death; he/she is closer to realities of life than peers in other streams. There is lack of research on how the next generation of medical students view the doctor-patient relationship. What is the self-image of a medical student? How is violence against their colleagues impacting them? What are the long-term consequences? Protests are only a manifestation of their frustration.

Ironically, most times the doctors who face violence in public facilities are young doctors! While the topic attracts attention, the voices are dominated by medical associations, activists, political leaders, government and administration officials. The whole narrative about violence is viewed from a transactional perspective of an event. The missing link is the perspective of these young doctors and how these instances shape their view towards the doctor-patient relationship! An understanding of these paradigms is important to address some of the challenges of healthcare in India

Locating the middle ground – The 7 Action Points

An adverse relationship is neither helpful for doctors nor for the public at large. While the patient is the reason the healthcare eco-system exists, the doctor is at the epicenter of healthcare delivery. If there is a hierarchy of societal needs, like Maslow’s hierarchy of motives, doctors will perhaps be in the ‘physiological’ needs zone at the foundation!

Doctors are the frontline of healthcare delivery and its most prominent face. Possibly, the doctor has become the face of everything that is wrong with the healthcare system! For a patient, a doctor is a doctor, irrespective of specialisation (Cardiology, Orthopaedics, Neurology, Haematology etc.) or whether they are in public or private healthcare. The changing socio-economic environment too puts stress on the doctor patient relationship, where about 70% of healthcare delivery happens through the private sector.

From a public relations perspective, beyond publicity, there are 7 actions the medical community can undertake to align with societal expectations and narrative, as follows:

- Medical associations have a role to play

There are two types of medical associations: one representing specialities (Cardiology, Orthopaedics, Neurology, Nephrology, etc.) and the second representing ‘medical interests’. Look around globally, the most credible voices are considered from medical institutions or medical associations of specialities. Beyond medical conferences, speciality medical associations have a role to play, based on their credibility and credentials to drive a positive narrative in their respective fields. It can not be a narrative of self-interest, but larger societal good.

2. Silence is consent

In communications, ‘no comment’ is also a comment, especially in critical situations or topics. Hoping ‘this too shall pass’ misses an important point: it impacts credibility, as stakeholders don’t hear your perspective and it just adds to the adverse narrative. Remaining silent is not an option. On the other hand, by not pro-actively addressing adverse narratives and reacting only to situations, can be perceived as ‘defending’. The communication approach is to be pro-active.

3. Practising ‘communication’

Communications is not just words, but actions as well. According to Edward Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud and one of the most influential public relations thinkers, for fruitful relationships, behaviours have to be aligned with societal expectations. Addressing the narrative through events and media has limitations: it is only the people from the fraternity that clap! Any redressal has to begin with an assessment of the situation: Perception Audit as is called in communications parlance.

4. The doctor – individual and as an institution

For a patient, or larger stakeholders, a doctor is a doctor, not withstanding the qualification or specialisation. Doctors represent the medical community. An amplification of one’s wrongdoing has a rub off effect on the whole community. Likewise, the good actions by most needs to be in public knowledge. Justice done, should be seen to have been done, is the dictum to be followed here.

5. Have a long term plan

Trust building takes time. The decline happened over a period of time, the redressal, not complete reversal will also take time. The collective of medical associations needs to have short, middle and long-term time horizons and action plans. The collective, is the important part.

6. Start at the point of strength

‘Magnanimity’ is one virtue stakeholders appreciate about their experiences with doctors. It can be the starting point of social engagement. The second area is supporting communications for medical students: they serve patients from across socio-economic backgrounds and are the future of the practice.

7. Neutral party intervention

In situations of conflict, when two parties are unable to find common terms, the ‘synergy’ as Stephen Covey call it, may be difficult. A neutral third-party intervention can help the cause, not as an arbitrator, but helping find the middle ground and trust building. Since doctors find neutrality missing in media narrative and government actions, the civil society and not-for-profit are two stakeholders who can play a role. The first evaluation benchmark can be in bringing down the incidents of violence against doctors both in private and public health.

The bottom line

If not for anything else, the medical fraternity and stakeholders owe it to the future generation of medical practitioners and the people they will treat, an opportunity of better mutual understanding and a healthy relationship. It has to be a two-way street: patient seeking succor against an illness and the doctor providing treatment. The relationship needs balance from both sides to prevent it from becoming an illness itself. Post Covid-19 offers the opportunity to reset the relationship and work towards a new normal.