Transparency, Trust, and the Problem of “Invisible Evidence” in Cancer Care

India’s pharmaceutical success has long rested on speed, scale, and affordability. For decades, regulatory frameworks and patent exceptions were designed to enable rapid entry of generics once exclusivity ended. In the small-molecule era, this approach was defensible—and often beneficial.

But as India moves deeper into the world of biologics and biosimilars, particularly in oncology, an uncomfortable question demands attention:

Are regulatory habits shaped in the generics era being carried forward into biosimilars—where the scientific, clinical, and ethical stakes are far higher?

Approval Is Not the Same as Verifiable Evidence

In clinical practice, regulatory approval is widely interpreted as a signal that a medicine’s evidence base can be trusted. Yet approval and public verifiability are not the same.

In India today, a biosimilar cancer therapy can receive approval based on a pivotal comparative clinical trial whose:

- full results are unpublished,

- protocols are not publicly accessible,

- and regulatory scientific assessments are unavailable to clinicians, patients, or independent researchers.

This does not mean trials were not conducted.

It means the evidence exists but cannot be independently examined.

In oncology, that distinction matters.

An Illustrative Oncology Approval

A recent Indian approval of a biosimilar nivolumab for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) illustrates the issue.

Public regulatory records confirm that:

- a Phase III, randomized, double-blind, comparative trial was conducted in India,

- the biosimilar was compared head-to-head with the reference product,

- expert committees reviewed the data,

- approval was granted for NSCLC,

- and a Phase IV post-marketing study was mandated.

What remains absent from the public domain is equally clear:

- no peer-reviewed publication of the trial,

- no conference presentation or abstract,

- no clinical study report,

- no regulator-authored summary explaining endpoints, results, or uncertainties.

The approval is real.

The trial is real.

The evidence, however, remains invisible to those prescribing and receiving the drug.

The Biosimilar Context—Clarified

This is not a novel drug approval. Biosimilars follow a comparability pathway, not a de novo efficacy pathway. Indian guidelines—aligned with global practice—allow:

- smaller Phase III trials than originator products,

- head-to-head comparison with the reference biologic,

- and extrapolation of indications without separate trials.

This pathway is scientifically legitimate. But legitimacy does not eliminate the need for public scrutiny. Without access to comparative trial data, clinicians cannot independently assess:

- equivalence margins,

- confidence intervals,

- safety and immunogenicity signals,

- or whether uncertainties were adequately addressed.

In cancer care, where decisions are often irreversible, that opacity is consequential.

The Bolar Exemption and the Creation of “Invisible Progress”

India’s patent law incorporates the Bolar exemption under Section 107A of the Patents Act. This provision allows generic and biosimilar manufacturers to:

- use patented inventions for research,

- develop manufacturing processes,

- generate clinical data,

- and submit regulatory dossiers before patent expiry, without infringing patents.

The Bolar exemption is lawful, internationally recognised, and essential for timely post-patent access. But when combined with India’s regulatory transparency gaps, it creates a structural side effect. During this phase:

- biosimilar development occurs entirely out of public view,

- trials may be completed,

- regulatory review may occur,

- yet no clinical evidence enters the public domain.

When approval and launch follow soon after patent expiry, clinicians encounter a finished product—without ever seeing the science that underpins it.

Regulatory Review vs Public Scrutiny

Indian regulators do review clinical data. That is not disputed. What is missing is public-facing accountability:

- Subject Expert Committee deliberations are not published in scientific detail,

- approval letters do not summarise trial outcomes,

- no equivalent exists to FDA approval packages or EMA public assessment reports.

This creates an asymmetry:

- regulators see the data,

- clinicians and patients must rely on trust alone.

In contrast, mature regulators treat transparency as integral to approval. Evidence is not only reviewed—it is explained.

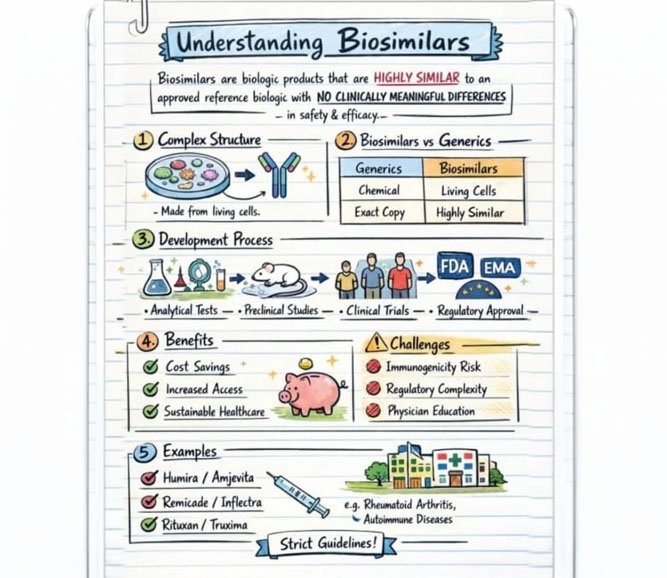

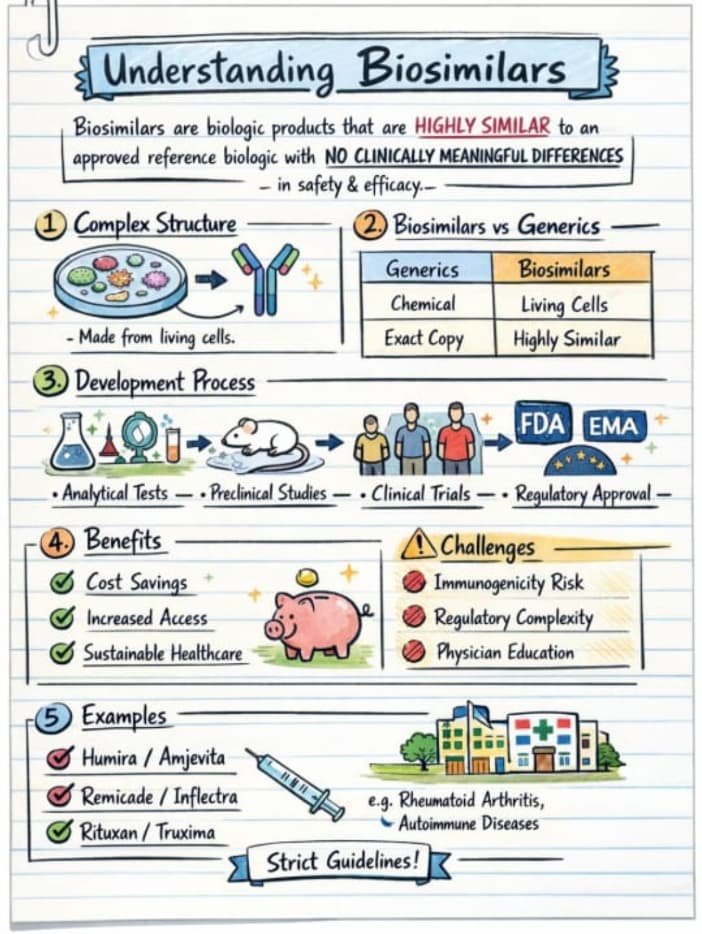

Why This Matters More for Biosimilars Than Generics

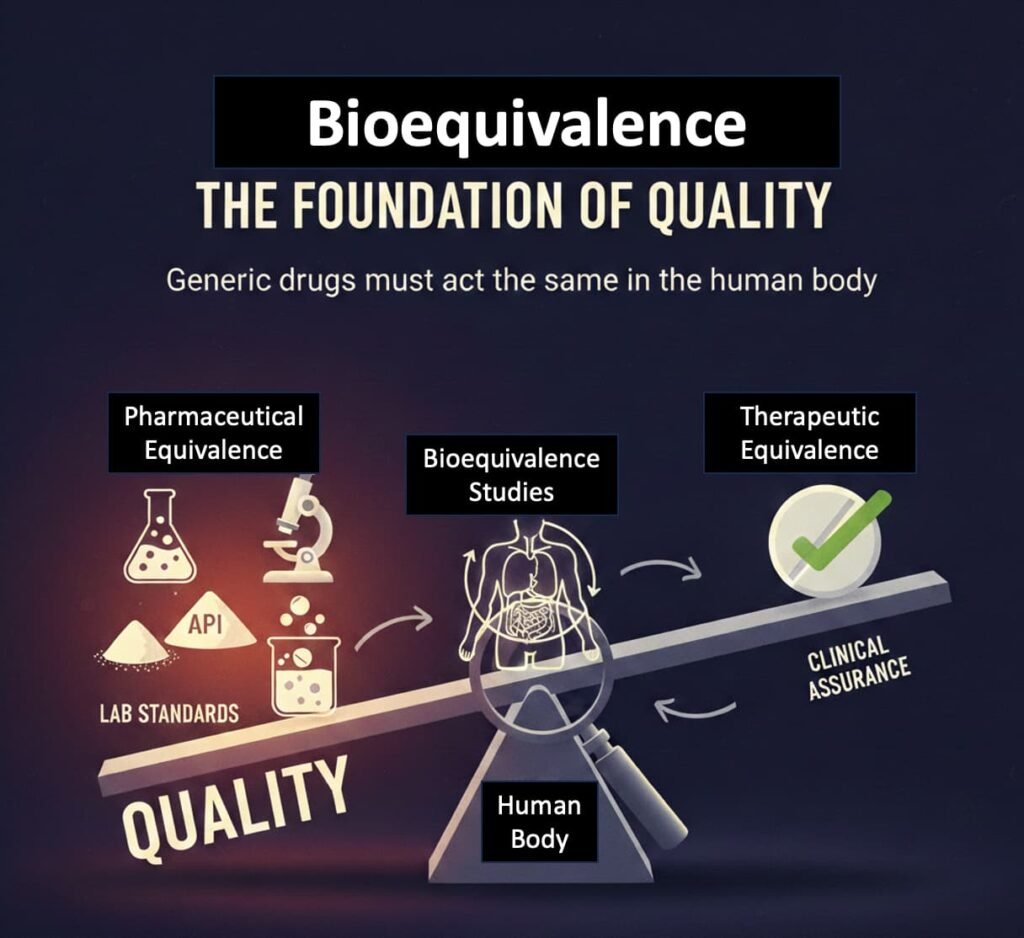

Generics regulation evolved around small molecules, where:

- bioequivalence testing is relatively straightforward,

- clinical uncertainty is limited,

- post-approval risk is modest.

Biosimilars are fundamentally different:

- structurally complex,

- sensitive to manufacturing variation,

- capable of triggering immune responses,

- often used when therapeutic options are few.

Applying low-transparency generics-era norms to high-risk biologics is a regulatory mismatch.

Extrapolation Magnifies the Problem

When approval for one cancer indication is extrapolated to multiple others, the single pivotal trial becomes the evidentiary foundation for all downstream use.

If that trial remains unpublished, the evidence base for several life-saving indications becomes effectively unverifiable.

Scientific defensibility does not remove the obligation of transparency.

Ethics, Consent, and Asymmetric Knowledge

Informed consent depends on the ability to explain not just benefits, but uncertainties. When clinicians cannot access primary evidence:

- uncertainty cannot be quantified,

- risks cannot be contextualised,

- consent becomes procedural rather than substantive.

This is not a failure of doctors or patients.

It is a system that withholds information from those expected to act on it.

A Structural Issue, Not a Scandal

This is not an allegation of misconduct or bad faith. It is a design problem:

- patent law encourages early, invisible development,

- drug regulation does not mandate public disclosure,

- together, they allow approval to precede transparency.

As India positions itself as a global biologics powerhouse, this gap becomes increasingly untenable.

What Needs to Change

If biosimilars are to command the same trust as their reference products, reform is unavoidable:

- Public scientific summaries at approval, akin to FDA or EMA assessments

- Time-bound disclosure of pivotal trial data, even for biosimilars

- Minimum transparency standards for extrapolated indications

- Clear communication of uncertainty, not just approval status

Access without transparency shifts risk downstream—to clinicians and patients.

The Bottom Line

The Bolar exemption is not the problem.

Biosimilars are not the problem.

Affordability is not the problem.

The problem is a regulatory system that allows clinical evidence to remain invisible at the moment it matters most.

In cancer care, trust cannot rest on approval alone.

It must rest on evidence that can be seen, questioned, and understood.

Editor’s Note: This article continues MedicinMan’s detailed examination of India’s pharmaceutical governance. After unpacking why the generics debate has long overemphasized price over quality and exposing structural oversight gaps in generic approvals, we now turn to a critical question for the next phase of Indian healthcare: as biologic therapies and biosimilars become central to modern cancer care, are the regulatory shortcomings of the generics era being carried over into this far more complex domain?

Part III in our ongoing examination of the Indian Regulatory Authority and the evolving quality story of domestic pharmaceuticals.

1. Quality, Not Price: Why the Generic Drug Debate Keeps Missing the Point

Explored how the national conversation on generics has focused on cost at the expense of quality.

🔗 https://medicinman.net/2026/02/quality-not-price-why-the-generic-drug-debate-keeps-missing-the-point/ via @MedicinMan

2. The Uncomfortable Truth About Indian Generics: Untangling the Conundrum

Delved into evidence gaps, production oversight challenges, and systemic regulatory blind spots in generics approval.

🔗 https://medicinman.net/2026/02/the-uncomfortable-truth-about-indian-generics-untangling-the-conundrum/ via @MedicinMan

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Appendix: High-Impact Sources Supporting Transparency, Biosimilars, and the Bolar Framework

A. Patent Law & Bolar Exemption

- Roche Products Inc. v. Bolar Pharmaceutical Co. (US Supreme Court)

- Indian Patents Act, Section 107A

- WTO TRIPS Agreement – Article 30 (limited exceptions)

B. Biosimilar Regulation

- WHO Guidelines on Similar Biotherapeutic Products

- Nature Reviews Drug Discovery – biosimilar regulatory science

- EMA Biosimilar Framework & EPARs

- FDA Biosimilar Review Pathway & Approval Packages

C. Oncology Evidence Standards

- The Lancet Oncology – cancer drug approval evidence analyses

- BMJ – clinical trial transparency and unpublished data

- JAMA Oncology – evidentiary thresholds in oncology approvals

D. Transparency & Ethics

- Declaration of Helsinki (2013)

- WHO Statement on Public Disclosure of Clinical Trial Results

- ICMRA joint statements on regulatory trust

E. India-Specific Analyses

- BMC Health Research Policy and Systems – CDSCO transparency

- Perspectives in Clinical Research – Indian regulatory ethics

- Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI) framework

Note: The author worked with a leading MNC – Asta Medica, Germany, inventors of Cyclophosphamide (Endoxan Asta) and Ifosfamide (Holoxan-Mesna) in the 1980s

Thanks to Amaninder Singh Dhillon for the editorial inputs.

All Images are AI Generated for Illustration Only. E&OE