The ongoing debate around branded versus generic medicines in India has once again climbed the headlines, nearly a decade after Prime Minister Narendra Modi proposed a law to mandate doctors to prescribe using only generic (salt) names, with the intent to make healthcare more affordable. While the original 2017 announcement sparked intense policy discussions and resistance from stakeholders, the issue remains unresolved even in 2025.

At the core of the matter lies a critical question: Can we ensure affordable access to medicines without compromising on quality and trust? The answer—based on recent developments in the pharma sector and regulatory policy—is both complex and evolving.

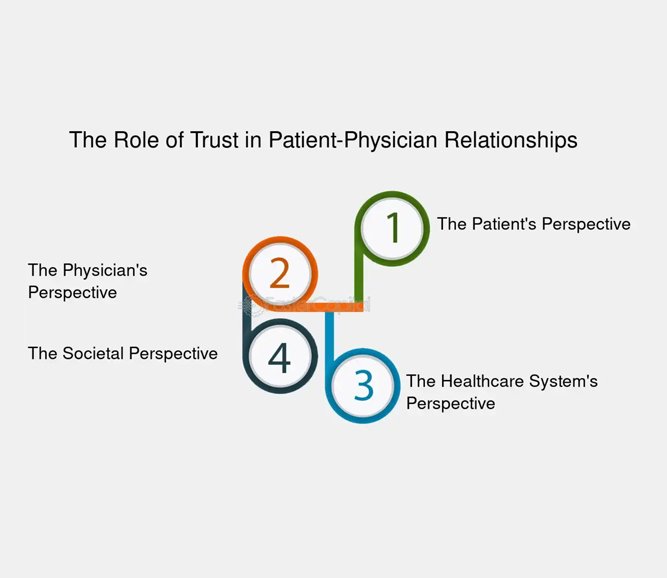

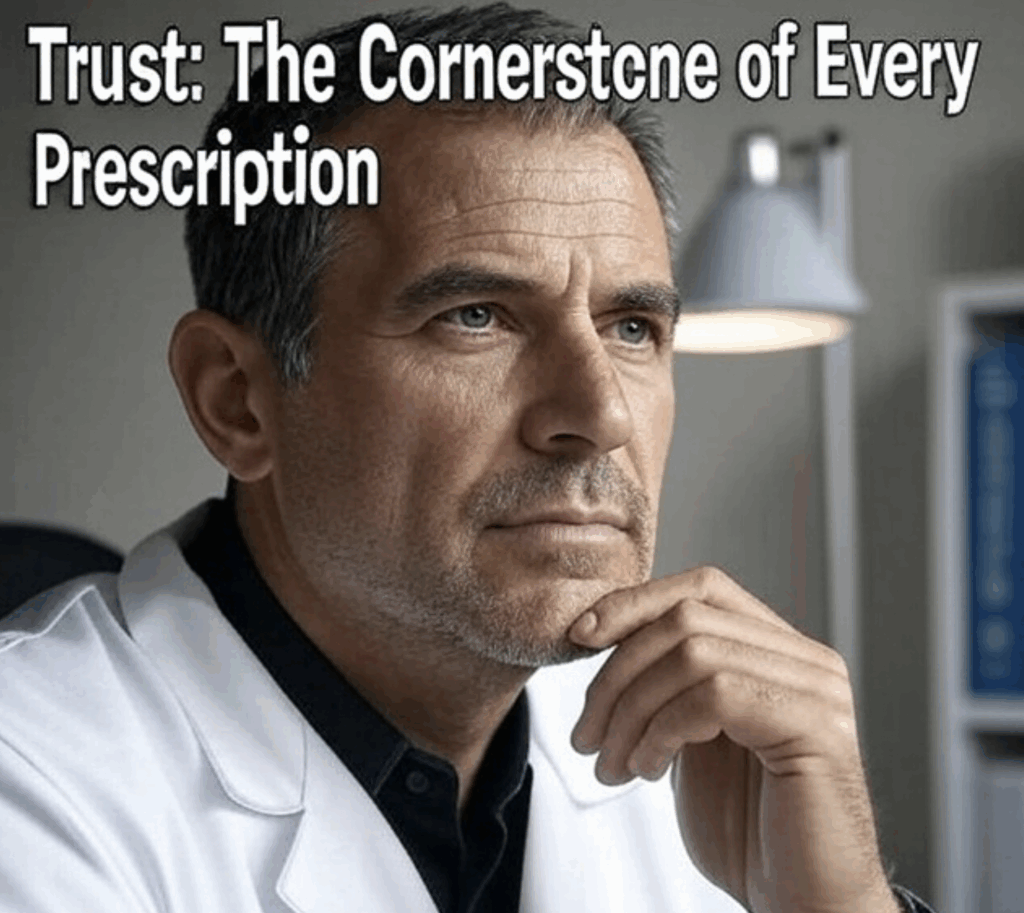

Trust: The Cornerstone of Every Prescription

Trust lies at the very heart of every decision a doctor makes—whether ordering a diagnostic test, selecting a medicine, or recommending a medical device. Such trust is never built in a vacuum; it must be anchored by concrete signals of quality and reliability. Ideally, this comes in the form of a statutory seal of approval from a recognized regulator—a clear assurance that a drug, device, or diagnostic meets stringent, universally accepted standards. In settings where regulators are either absent or their oversight is perceived as inconsistent, both doctors and patients must turn to alternative marks of trust. Here, the reputation of a company—demonstrated through a consistent track record of quality and ethical practices—becomes the critical factor in inspiring confidence and guiding safe, effective clinical choices.

What Makes a Medicine “Generic”?

In the global medical ecosystem, a generic drug is a pharmaceutical product that is bioequivalent to its brand-name counterpart—delivering the same dosage, safety, strength, quality, performance, and intended use, but at a significantly lower price.

“All generic manufacturing, packaging, and testing sites must pass the same quality standards as those of brand-name drugs.”

— U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA)

This equation holds true in the U.S., Europe, and Latin America, where generics come into the market post-patent expiry of the innovator molecule, offering significant cost savings. However, the application of this model in India presents several unique challenges.

India’s Distinct System: The Reality of “Branded Generics”

India doesn’t just have generics—it has something far more complex: branded generics. These are non-patented molecules sold under brand names by domestic manufacturers. While they are technically generics, they have the visual and marketing appeal of innovator brands and dominate India’s ₹2.3 lakh crore domestic pharma market.

But here’s the fundamental issue: unlike in developed nations, where drug quality is assured by strong regulatory oversight, Indian generics often suffer from variable manufacturing quality, poor bioequivalence data, and a weak enforcement infrastructure.

Thus, the Indian generics debate isn’t just about cost—it’s about assurance of quality. And in the absence of universal confidence in the manufacturing ecosystem, most doctors continue to prescribe branded generics from reputable companies like Cipla, Sun Pharma, Glenmark, or Dr. Reddy’s, believing that these companies are less likely to risk their reputation over substandard products.

Why Quality Matters More in India: The Telma Case

A compelling example is Glenmark’s Telma, a brand based on Telmisartan, used for treating hypertension. Since its launch in 2003—when another drug, Ramipril, dominated the market—Telma has grown into a ₹1,000+ crore brand with 16 successful extensions.

“Telma’s success didn’t rest on price alone. It was built on consistent quality, niche positioning, therapeutic reliability, and professional trust.”

— MedicinMan, 2025

Glenmark’s long-term vision, sound R&D investment, trust among healthcare professionals, and minimalist but strategic marketing were instrumental in making Telma one of India’s top antihypertensive brands. The Harvard Business Review even studied it as a case in brand-building.

This success story illustrates an important truth: large pharmaceutical companies have more to lose from quality lapses, especially when competing with other top brands. This reputation-driven risk ensures that established brand names often meet higher internal quality standards, even within a somewhat fragmented regulatory context.

NDDS: All Generics Are Not the Same

Further complicating the generics-versus-brand debate is the growing number of branded generics employing Novel Drug Delivery Systems (NDDS). These include:

- Sustained release diabetes medications (e.g. Metformin SR, Gliclazide MR)

- Mouth-dissolving painkillers for faster relief

- Metered dose inhalers for asthma

- Extended release epilepsy medications

“Drugs like Metformin-SR and Gliclazide-MR have pharmacokinetics and clinical benefits that are formulation-dependent. Generic copies don’t always match up.”

— Dr. Puneet Dhamija, AIIMS Rishikesh

NIH Article

Prescribing just the salt name, without product-specific knowledge of the delivery system, puts too much faith in the retail pharmacist’s discretion. And here lies another fault line.

The Retail Reality: A Supply Chain Not Built for Such Trust

India has a massive network of over 800,000 drug retailers, many of whom lack rigorous pharmacy education and are driven almost entirely by commercial motives. These retailers typically stock what sells best, often gravitating toward high-margin products, regardless of their clinical value.

Expecting these retailers to correctly substitute branded NDDS products with unbranded generics isn’t just unrealistic—it’s dangerous. Until we have a fully trained, certified community pharmacist model (as seen in the U.S. or EU), putting the responsibility of substitution in their hands isn’t patient-first.

In fact, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) once penalized India’s largest chemist lobby (AIOCD) for imposing restrictive practices on drug distribution, pointing to the entrenched commercial pressures in the system.

Necessary Reforms: Strengthening the Foundation First

The government has taken important steps in recent years. In January 2023, the Union Health Ministry mandated that all drug manufacturers must upgrade to WHO-GMP norms (Schedule M Revision). However, only about 2,000 of India’s 10,000 drug firms comply, and many have until 2026 to meet the deadline.

This gap makes clear that mandatory generic prescribing is premature unless bioequivalence data, quality metrics, and supply chain regulations are strengthened concurrently.

A Phased, Collaborative Path Forward

Reforming drug prescription norms in India requires a time-bound, phased rollout, not a knee-jerk mandate. Here’s a roadmap to consider:

- Pilot Implementation: Begin with select high-prescription therapeutic classes like NSAIDs and antibiotics.

- Transparency: Mandate bioequivalence and quality disclosures for all drug makers.

- Retailer Training: Certify pharmacists through government-medical college partnerships.

- Patient Education Campaigns: Gradually inform the public about generics, substitution, and drug efficacy.

- Jan Aushadhi Expansion: Enhance inventory, branding, and reliability of Ayushman Bharat’s public pharmacy network.

Trust: The Cornerstone of Every Rx

Industry specific marketing: Pharmaceutical Marketing Ethics: Prescribing Trust: Ethical Marketing in the Pharmaceutical Industry – https://www.fastercapital.com/content/Industry-specific-marketing–Pharmaceutical-Marketing-Ethics–Prescribing-Trust–Ethical-Marketing-in-the-Pharmaceutical-Industry.html

Trust lies at the very heart of every decision a doctor makes—whether ordering a diagnostic test, selecting a medicine, or recommending a medical device. Such trust is never built in a vacuum; it must be anchored by concrete signals of quality and reliability. Ideally, this comes in the form of a statutory seal of approval from a recognized regulator—a clear assurance that a drug, device, or diagnostic meets stringent, universally accepted standards. In settings where regulators are either absent or their oversight is perceived as inconsistent, both doctors and patients must turn to alternative marks of trust. Here, the reputation of a company—demonstrated through a consistent track record of quality and ethical practices—becomes the critical factor in inspiring confidence and guiding safe, effective clinical choices.

Final Word: A Reform Too Important to Rush

The practice of prescribing by salt name may work well in regulated ecosystems like the U.S., where all generics are therapeutically equivalent and pharmacists are highly trained. But in India, where brand reputation often substitutes for missing regulatory and clinical assurance, a blanket generics-only law without capacity building is not patient-friendly—it’s risky.

The story of trusted brands like Telma, and thousands of others like it, shows that quality, consistency, and brand trust cannot be legislated overnight—they are built over decades of ethical business and clinical partnership.

Legislative compulsion must be supported by credible infrastructure, pragmatic timelines, and stakeholder dialogue—anything less is sure to compromise the very patients these reforms aim to help

References

- U.S. FDA. Understanding Generic Drugs

- Soans, Anup. “How Did Telma Become a 1000+ Cr Brand?” MedicinMan, Feb 2025

- Dhamija, Puneet et al. “Only Generics: Is India Ready?” Indian Journal of Pharmacology

- CCI India. Order against AIOCD (2013)

- Economic Times. All Indian Drug Makers to Meet WHO-GMP Standards

- Jan Aushadhi Scheme. PMBJP Official Portal

Author: Anup Soans is Editor of MedicinMan.net and former Executive Director of the Indian Journal of Clinical Practice. He writes critically on pharma industry practices, ethical marketing, and public health policy.