Physical assault on healthcare workers, especially doctors is on the rise. The perpetrators are anguished relatives, a mob or even a politician flexing his ‘executive muscles’. While the doctor at the receiving end is left physically and emotionally scarred for life, a genuinely aggrieved family may be left utterly helpless in the face of a medical misadventure. It angers the medical fraternity and dims their faith in society. Collectively they dwell upon years of hard labour, compare respect and remuneration earned by doctors abroad and start feeling hard done by. The public watches all this from a different window: That of poor access to reliable medical care, hefty bills, stories of medical negligence resulting in death and reacts with a ‘what else did they expect’?

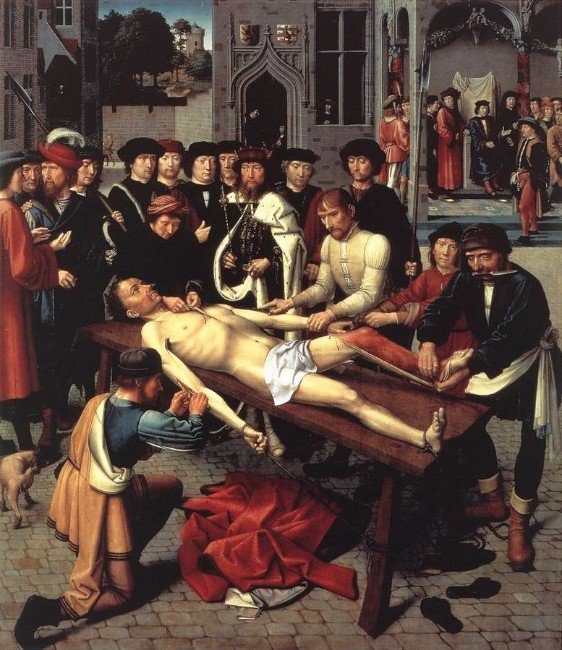

While the variables in this equation are different in each case, the sum total is detrimental to the society. Physical retribution – medieval and mindless, is pushing the Doctor-Patient relationship into a vortex of mutual mistrust, an antithesis to what it should be.

Even as this seems entirely without reason, here is an attempt to unravel what could be at the root of this impasse.

It is Ok to hit someone: Physical retribution for a perceived wrong has always been acceptable in our society, for example: Spanking kids at home or a lathi wielding policeman.

Bipolar perception of the medical profession: ‘Noble profession’, a calling and not a job that pays the bills. Monetary returns puts a practitioner in the ignoble bracket. Doctors on one hand are deified (demigod status) and on the other vilified (killed the patient, looters). We celebrate IITians making big money but not doctors. Corollary – an entrepreneur hitting gold is a genius, but a doctor well off, must be unethical.

Skewed perception of how medical science works: Mystics were medical men in ancient societies. Today it is a science, but not perceived as that. A dying man brought to the mystic always walked home, same would be the expectation today. If a business fails, it was an idea that didn’t work. If treatment fails – it must be a botch up. A broken gadget may be beyond repair, but not a patient in a doctor’s hands. From such ungraded expectations stems the potential for things to take an ugly turn.

An unwanted profession dealing with an unwanted condition, namely Ill health: If possible, we would wish away death and diseases, hospitals and doctors. A hospital is not a holiday resort, but it too costs money. And the scenario of an adverse outcome like death simply becomes unacceptable.

Doctors Associations are not patient advocates: Medical Associations functioning less as trade unions for doctors and more as advocacy for patients would have created goodwill. Doctor’s interests on occasions are seemingly in conflict with those of patients.

Lack of a usable, good grievance redressal mechanism: A bipartisan, fair, swift redressal system would benefit both parties. These attributes are lacking in existing framework and violence is then seen as swift retribution.

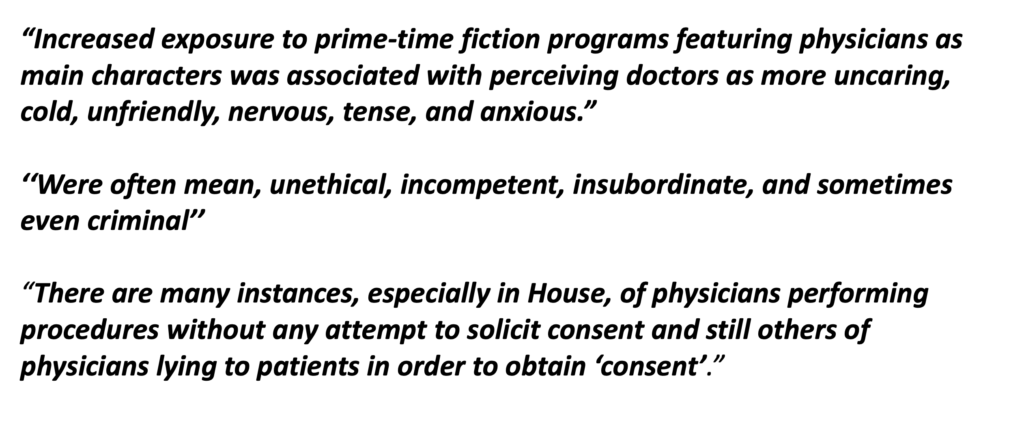

Irresponsible portrayal in media: It makes for cheap entertainment to sensationalise medical malpractice in movie scripts: pre-release screening is done for religious leaders when disruption in communal harmony is anticipated. Is loss of mutual trust between doctors and patients less incendiary?

45:3, 499-521, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/the-academy/_docs/TV%20Hopkins.pdf

Unethical medical practice and lack of transparency: It is a fact that murky practices exist and when things are investigated there is no transparency. Not enough has been done to demonstrate that the medical fraternity is concerned about rooting this out.

Inadequate and dysfunctional government healthcare: Successive governments have not invested in and prioritised universal healthcare. Private healthcare is filling the gaps albeit patchily and at a cost. The desperation arising out of poor access to emergency lifesaving interventions for a family member (Lack of awareness/distance/poorly equipped and manned facilities) can be very acute. Rage is naturally the first reaction when a loved one dies.

We need a two pronged approach to this complex problem: Immediate containment of such incidents and measures to build bridges with the public. While the Government should be responsible for the first, doctor’s initiative should drive the latter.

‘Zero tolerance’ policy: Any workplace, let alone hospitals, should have zero tolerance for a physical or verbal abuse policy. It should be a no-event, a non bailable offence. Existing provisions in the legal framework should be deployed in every such instance.

An Appellate for conflict resolution:

An appellate to arbitrate without fear or favour is needed. The two main features of such a body should be-

A) Fast-tracking: deadline of 6-8 weeks for resolution

B) Funding: a bereaved family with no financial reserve should be able to readily get help.

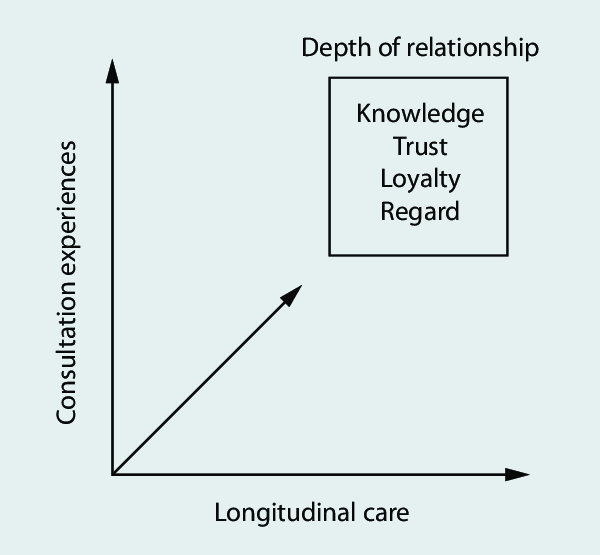

Training in communication skills: Doctors understand diseases and medicines well, but not the people or society in which these illnesses occur. They need better communication skills to set expectations and manage adverse outcomes. Medical curriculum should include working the shopfloor skills.

One team on the same side of the game: The adversary is the illness, not the doctor or the patient. Building trust is a difficult but rewarding process: IMA and other doctors associations should lobby for a higher health budget and should push for an appellate. We should stop airbrushing with ‘there are black sheep in every profession’. The onus is on us – we need to reflect on how to clean our stables. Self-scrutiny and self-regulation is always better. Left to outside forces, sensibility gives way to sensationalism (like ‘crackdown’ on hospitals).

With the doctor-patient trust at an all-time low, change is an uphill task. The immediate need is of zero tolerance to violence at the workplace. There should be no delay in revamping a patient grievance redressal system. Consistently, doctors should strive to be advocates for patients and equip themselves to communicate better. Healthcare facilities should be a Safe space for both the patient and healthcare worker. The first principle of medicine ‘Primum non nocere’: First do no harm should apply to both the physician and the patient.

Dr Rajath Athreya, MBBS, MD (Paediatrics), MRCPCH (UK), CCT (London)

Dr Rajath Athreya is a leading consultant paediatrician and neonatologist based out of Bengaluru. He completed his post graduation from Bangalore Medical College with top honors. He worked in the NHS, UK for a decade, training in some of the top hospitals in London before relocating to Bengaluru seven years ago. He strongly believes in practicing family focused evidence-based medicine which is child centric. He is a passionate teacher with an interest in simulation-based learning. He trains both medical doctors and corporate employees in soft skills and effective communication.