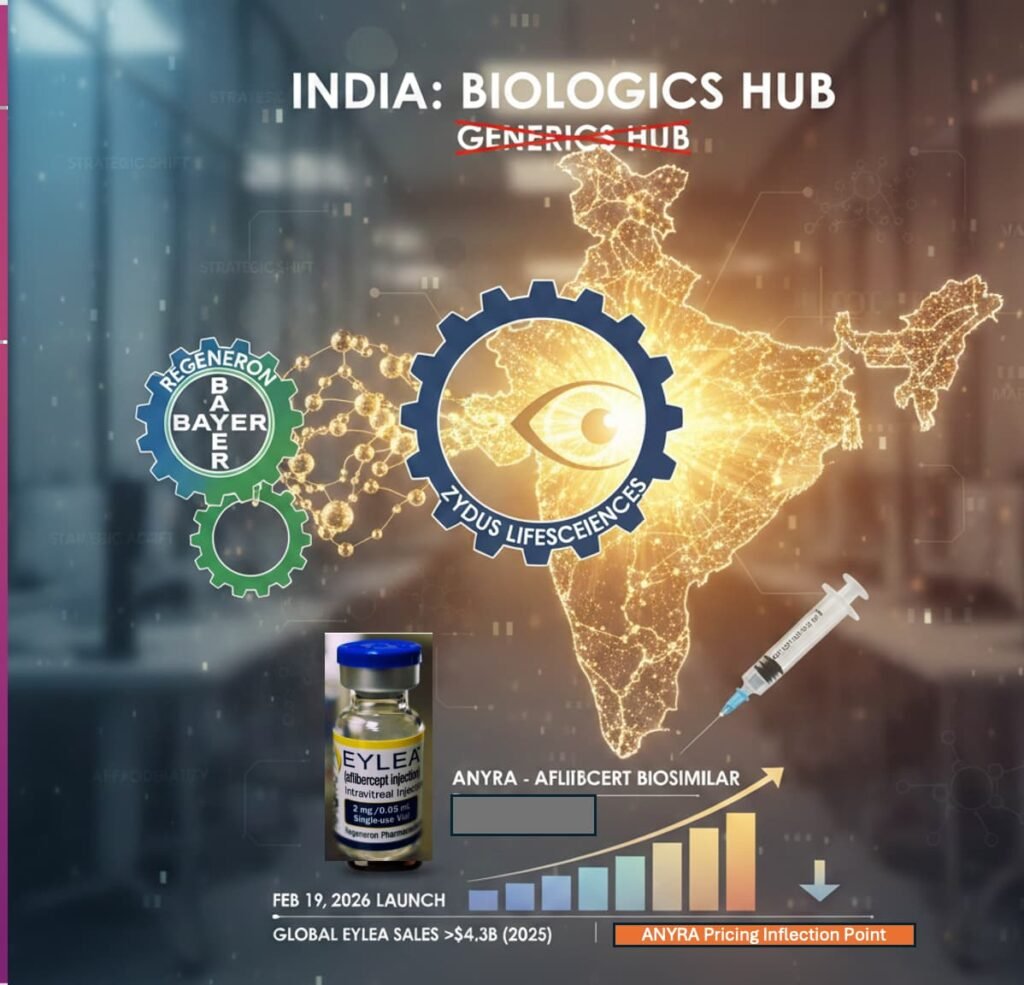

When Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Bayer AG signed a licensing agreement with Zydus Lifesciences to commercialise aflibercept in India, they did something telling. They chose negotiation over confrontation. That decision signals a structural shift in how global biologic innovators now view India: not as a peripheral generics market to police — but as a biologics arena to strategically engage. At the centre of this development is Aflibercept, marketed globally as Eylea, one of the most commercially successful ophthalmic biologics in the world.

This is not just a biosimilar launch. It is a pricing inflection point.

The Drug: High-Precision Biologic, Not a Commodity

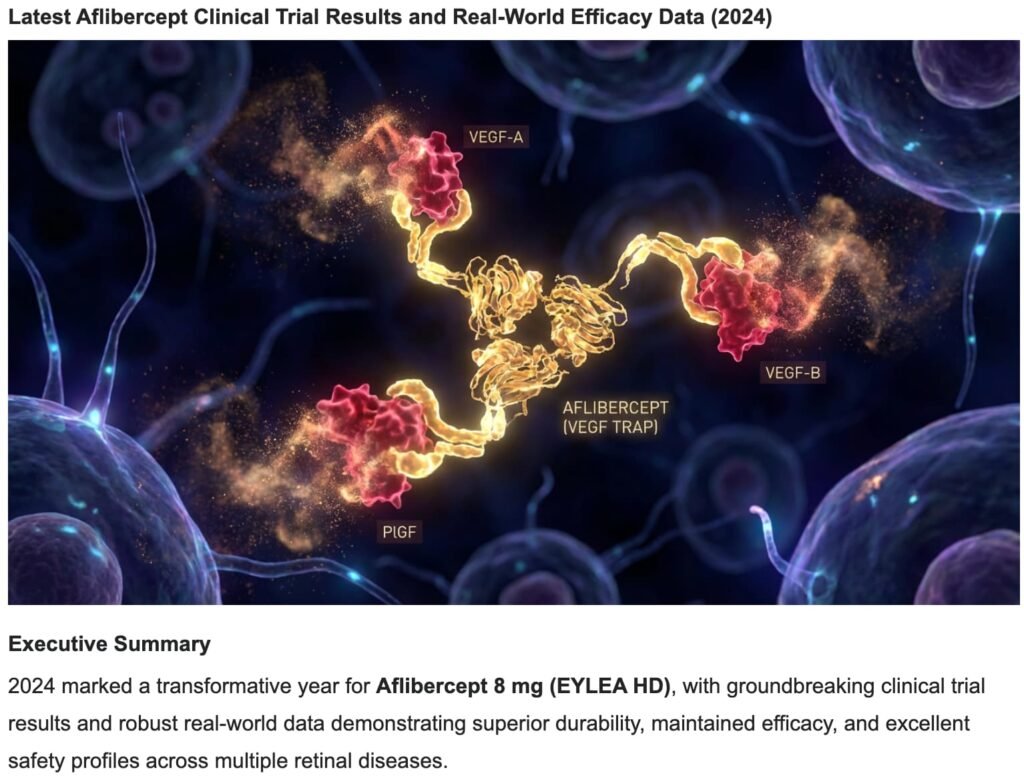

Aflibercept is a recombinant fusion protein that functions as a VEGF trap. VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) is a protein that stimulates abnormal blood vessel growth; a “trap” binds to it and neutralises its activity. Aflibercept specifically binds:

- VEGF-A

- VEGF-B

- Placental Growth Factor (PlGF)

By neutralising these pathways, it reduces abnormal angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) and vascular leakage in the retina — the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye.

Indications include:

- Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration (wAMD)

- Diabetic Macular Edema (DME)

- Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)

- Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

Treatment requires repeated intravitreal injections — typically monthly loading doses followed by maintenance dosing every 4–8 weeks. This makes aflibercept a recurring, long-duration therapy model. According to annual filings by Regeneron, global Eylea revenues were approximately $9 billion annually in recent years, underscoring the molecule’s commercial scale.

India’s Epidemiological Reality

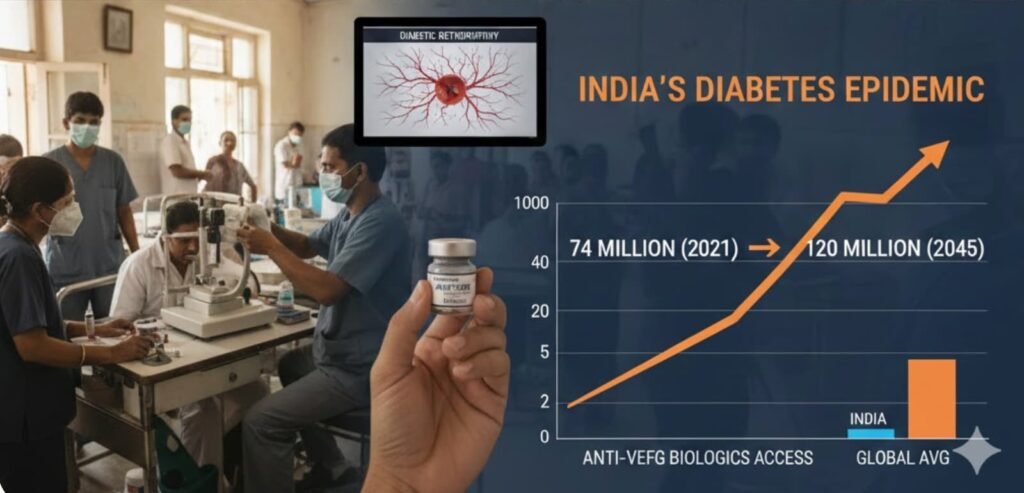

India is home to one of the world’s largest diabetes populations. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th Edition, 2021) estimates that India has roughly 74 million adults living with diabetes, projected to exceed 120 million by 2045. Published Indian studies in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology report diabetic retinopathy prevalence ranging from 16% to 28% among diabetics, depending on the cohort studied. This is not a marginal disease segment. It is a high-burden, expanding public health challenge. Yet access to premium anti-VEGF biologics has historically been constrained by price.

The Pricing Gap That Shaped Prescribing

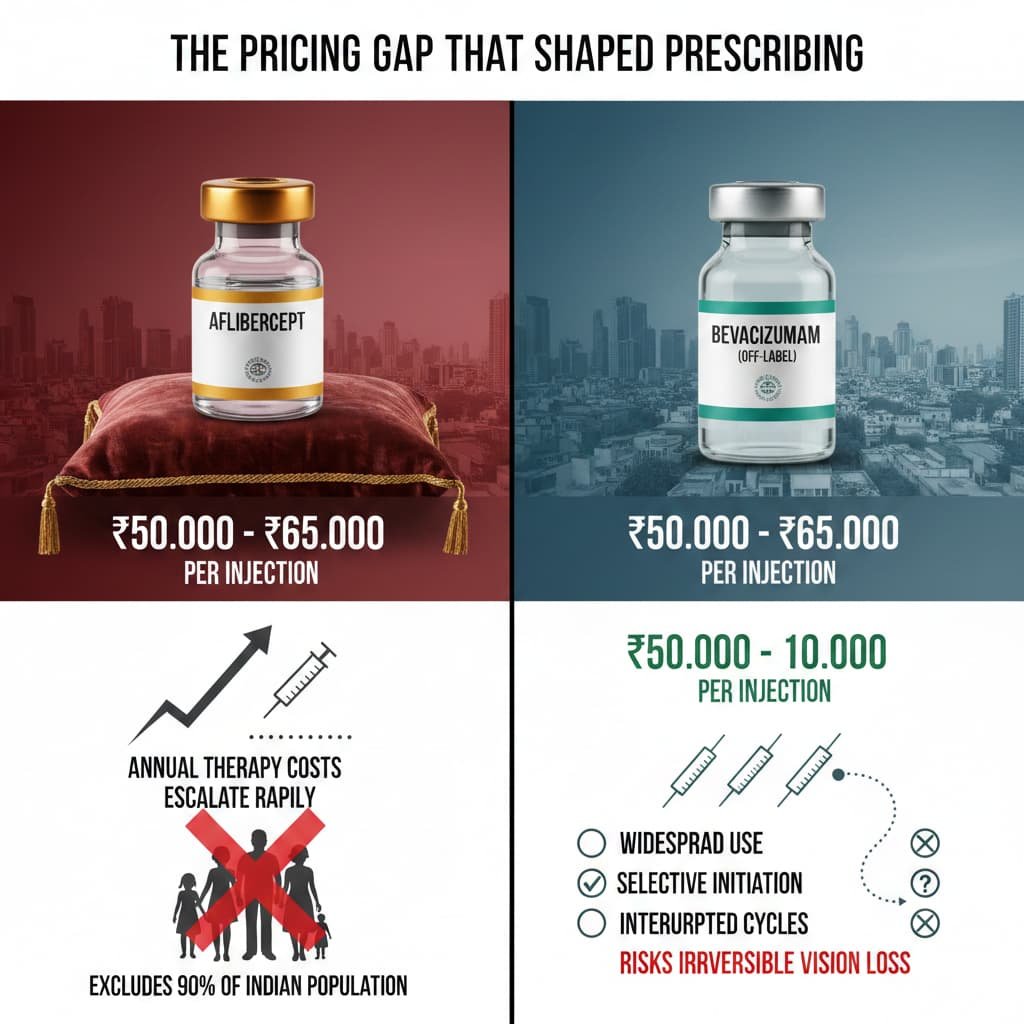

In the Indian private market, innovator aflibercept has often been priced in the ₹50,000–₹65,000 per injection range, as reported in Indian business media and hospital pricing disclosures.

To contextualise: this places a single aflibercept injection beyond the monthly per capita income of approximately 90% of the Indian population, according to government economic survey data. The implication is not merely that therapy is expensive — it is that the prevailing pricing model effectively excludes the mass market entirely.

Given:

- 3 loading doses

- Ongoing maintenance injections

Annual therapy costs escalate rapidly. This pricing reality led to:

- Widespread use of lower-cost off-label bevacizumab

- Selective initiation of therapy

- Interrupted treatment cycles in cost-sensitive patients

In ophthalmology, incomplete therapy does not merely reduce revenue — it risks irreversible vision loss.

Why Licensing Matters

Instead of contesting biosimilar entry through prolonged litigation, Regeneron and Bayer opted for a licensing framework. That approach achieves four things:

- IP Risk Mitigation — Reduces legal uncertainty and avoids the unpredictability of Indian court outcomes on biologic patents.

- Revenue Participation — Preserves economic interest in the market through royalty or supply arrangements, rather than ceding it entirely.

- Orderly Market Entry — Enables controlled pricing evolution rather than disruptive discounting.

- Therapy Continuity Protection — In retinal disease, irregular treatment driven by cost sensitivity can produce poor clinical outcomes, which indirectly damages the molecule’s real-world efficacy reputation. Licensing creates a pathway to more consistent patient coverage, preserving clinical credibility even at adjusted price points.

This is strategic realism. Emerging markets like India are too large to ignore, yet too price-sensitive to defend purely through enforcement. Licensing is not surrender. It is recalibration.

The Biosimilar Effect

Historically, Indian biosimilars have entered at a 20–40% discount to innovator pricing, according to industry analyses reported by ETPharma and IQVIA commentary.

If aflibercept follows a similar trajectory:

- Per-dose costs could decline materially

- Annual therapy burden could ease

- The treated patient pool could expand

What remains uncertain is whether Indian pricing will follow the European biosimilar discount curve — typically 30–50% in mature markets — or whether the volume potential of the Indian diabetes population will support a shallower discount. The licensed nature of this entry, as distinct from purely competitive biosimilar launches, may incline toward the latter. In chronic diseases, price elasticity often expands the market rather than merely redistributing share. In retina, that expansion may directly translate into preserved vision for thousands.

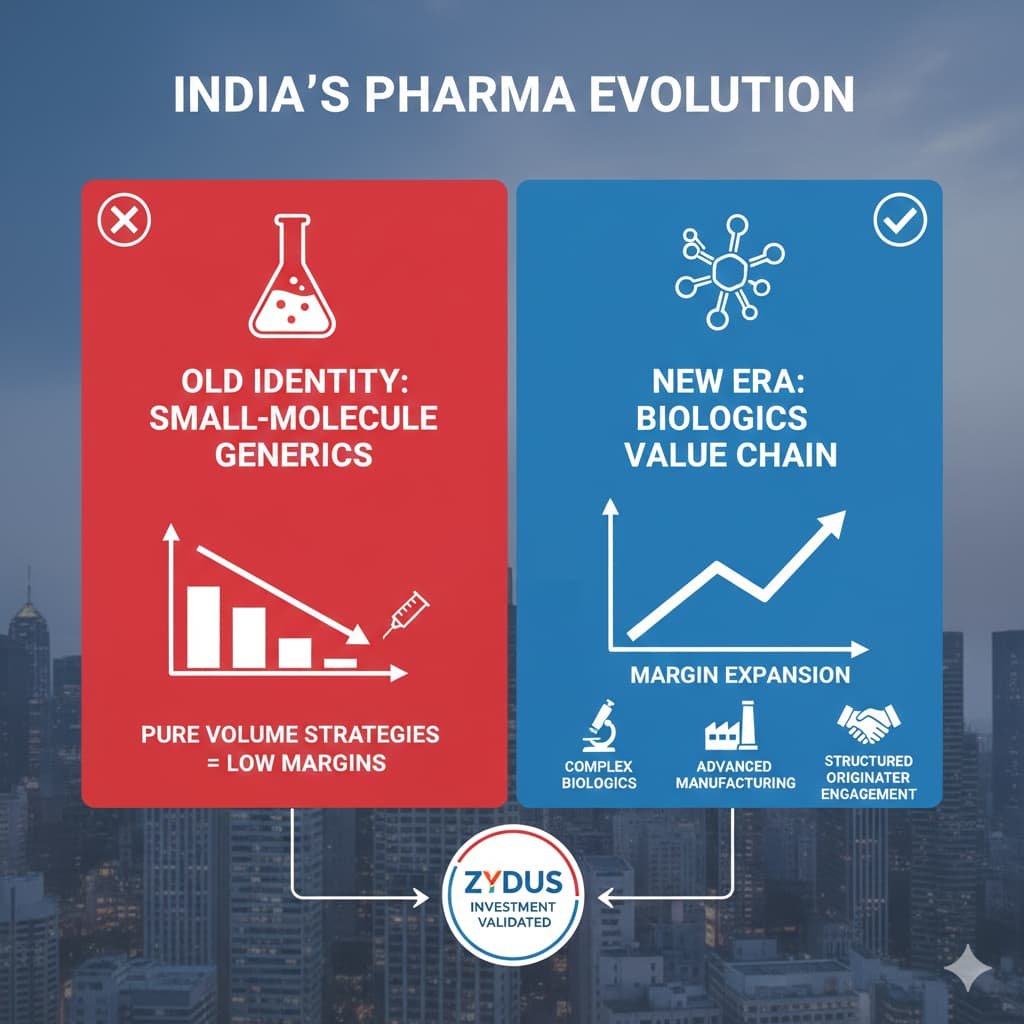

The Bigger Shift: From Volume to Value

For decades, Indian pharma’s global identity was anchored in small-molecule generics.

Now the pivot is unmistakable:

- Complex biologics development

- Advanced manufacturing and comparability capability

- Structured engagement with originators

- Margin expansion beyond pure volume strategies

Zydus itself, for instance, has invested in biosimilar R&D facilities and demonstrated comparability expertise in regulated markets — capabilities that did not exist in India a decade ago. The aflibercept licence is thus a validation of existing infrastructure, not a speculative bet.

Aflibercept’s licensed entry reflects a broader industry evolution: India is no longer only reverse-engineering molecules. It is negotiating its place in the biologics value chain.

What This Prefigures

The aflibercept licence will not be the last of its kind. As India’s diabetes burden deepens and its biologic manufacturing capability matures, originator portfolios in oncology, immunology, and metabolic disease will face similar calculations. The question is not whether more such deals will occur — it is which molecules will follow, and whether the pricing inflection point now established becomes a template or remains an exception.

The Real Question

The debate should not be framed as innovator versus biosimilar. The real question is this: Can India balance innovation incentives with access expansion?

If licensing-backed biosimilars reduce cost barriers while preserving value for originators, this may represent a sustainable middle ground. Not price collapse. Not monopolistic persistence. But calibrated competition.

Sources

- The Economic Times (ETPharma) — Reporting on the licensing agreement between Regeneron, Bayer, and Zydus for aflibercept commercialisation in India (February 2026).

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Annual Reports & SEC Filings (2022–2023) — Eylea revenue disclosures (~$9 billion annually).

- International Diabetes Federation, IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th Edition (2021) — India diabetes prevalence data and projections.

- Indian Journal of Ophthalmology (ICMR- and AIIMS-linked epidemiological studies) — Diabetic retinopathy prevalence data in Indian populations.

- IQVIA industry commentary and ETPharma reporting on biosimilar pricing trends in India (20–40% discount benchmarks).

- Indian hospital pricing disclosures and business media coverage reporting aflibercept pricing ranges in private markets.

- Government of India Economic Survey (latest available) — Monthly per capita income estimates for contextualising therapy affordability.

All Images are AI Generated for Illustration Only. E&OE